Far From Home: Children’s coping strategies on the Central Mediterranean Route

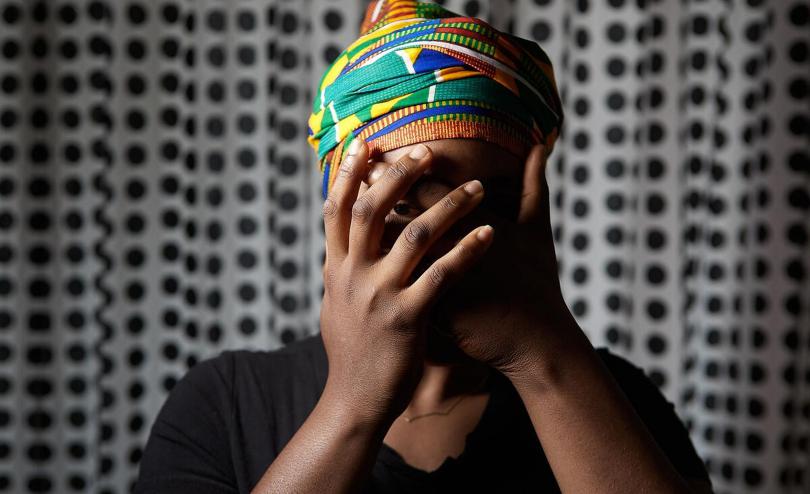

Young woman trafficked from Nigeria to Italy at the age of 16. Save the Children.

Omar*, a 17-year-old boy, used to live in Eritrea with his mother and two brothers. When his older brother was killed as a result of communal violence, his mother persuaded him to leave the country to avoid becoming entangled in a cycle of revenge and seek better life prospects. Against his will and with limited finances, Omar moved to Sudan. Undocumented, out of school, and unable to find a job, Omar was at risk of harassment and detention. On top of this, he feared that his brother's murderers would ultimately come after him.

When Omar learnt that a group of peers intended to migrate to Libya with the help of a smuggler, he joined them. He had no idea of the risks he would encounter along the way. Once in Libya, the children were transferred to traffickers, held for ransom, and tortured. After two months, a rival armed group stormed the location in al-Kufra, where they were held captive. Omar managed to escape in the commotion, while others went missing or died. Omar eventually reached Tunisia.

This is not only Omar's story. Every year, tens of thousands of children find themselves on a hazardous journey from the East and Horn of Africa to Europe along the Central Mediterranean Route (CMR) that stretches from sub-Saharan Africa. They are driven by conflict, climate crisis, persecution, economic hardship, and a shortage of opportunities in their home country.

Desperate families scrape together precious funds to pay smugglers, who very often are someone they know and trust in their community, to safely transport them and navigate international borders toward a more promising life. Tragically, many of these children are subject to an accumulation of risks and are unable to cope, increasing the likelihood of bonded or forced labour, sexual exploitation, ransom, kidnapping, and abuse.

While children are able to articulate the pain and the impact of such events, they don't necessarily describe their situation as that of trafficking or exploitation but as a necessary step in their journey. In fact, many children only perceive their treatment as trafficking if there is a sale or exchange of money.

Samuel Hall recently undertook a qualitative research study for Save the Children's Migration and Displacement Initiative, “Tipping points to turning points: How can programmes and policies better respond to the risks of child trafficking and exploitation on the Central Mediterranean Route?” focusing on how smuggling can become trafficking along the CMR. This study was mandated by the Swiss Agency for Development and Co-operation (SDC) and commissioned by the Swiss State Secretariat for Migration (SEM) to inform the East African Migration Routes (EAMR) project in Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan.

The CMR is a long journey, no matter where it begins. Risks manifest more frequently and with more severity during border, desert, and sea crossings, especially when children cannot access their support systems. Poorly supervised camps, and detention facilities, bargaining with smugglers without adult relatives, and facing border enforcement personnel make the circumstances all the more challenging. Moreover, existing vulnerabilities, traits, and ethnic backgrounds of children can increase the dangers of various forms of exploitation. The research brought to light the coping mechanisms that children use to shield themselves from the worst consequences of exploitation on route. Some of these strategies, however, may put children in harm's way.

Far from home: friendships, support, and risks on the move

A child migrant's protective ecosystem diminishes as they move further away from their community of origin. During the journey, other child migrants become a source of moral support. These connections frequently cut beyond national and cultural boundaries, bound by the shared challenges they face. However, these connections are often fleeting and the children separate, alone and in danger once again: 'When [my friend] was down, I lifted him, and when I felt tired, he helped me to rest till we reached Tripoli. There, each of us went on our way,’ said Shaba, a 14-year-old boy from Eritrea.

Children who migrate alone often inform their families and seek their support only when they reach border points or enter transit countries. In these situations, the ability of families to provide meaningful support is limited by a lack of preparation and available resources.

Some children choose to travel with unrelated but trusted adults - neighbours or family friends. The child gets protection, while the adult increases their odds of being admitted to the destination country. These transactions make children feel safer during the journey, but they also reinforce the perception of migrant children as commodities for adults, open to the abuse of exploitative individuals.

Children travelling with their families are provided with a significant source of support but they may also become a source of risk during transit. Under extreme stress and hardship, parents cannot be assumed to be capable of providing meaningful protection to their children. Accompanying adults may conceal critical information from migrant children (such as information about contact persons, transit points, or risks) to avoid exposing migrant children to stress. However, this puts migrant children at risk in cases of unanticipated family separation.

The risk of rape is often considered a price to pay: girls’ coping strategies

Boys and girls on the move face different risks and resort to different coping mechanisms. Among girls, sexual abuse and the exchange of sex for basic needs is common in large migration hubs. These practices range from sexual services offered in separate rooms at beauty parlours and teashops in Khartoum to brothels in Libya and temporary marriages in Egypt. Girls' prevention strategies consist primarily of travelling with trusted adults, maintaining close contact with their family and diaspora, and blending in with the local population to be less visible. Some migrant girls also anticipate adverse events and plan to mitigate unwanted consequences. For example, many girls interviewed expected to be raped on the journey and started taking contraceptive pills before they departed as a mitigation measure. According to a social worker in Tunisia: 'girl victims consider the risk of raping as normal… a sort of price to pay’.

'When I started the journey, one of my relatives advised me to use birth control for a long time to avoid unwanted children, which may have resulted from rape. This advice was helpful to me since I had been raped numerous times, and it stopped me from becoming pregnant,' said Dani*, a migrant girl from Ethiopia.

While birth control and emergency contraception are a means to limit some of the long-term repercussions of sexual and gender based violence during migration, they can do little to address other immediate healthcare concerns or longer-term psychological impacts arising from sexual exploitation and trafficking.

A consolidated effort across borders - the way forward

When no legal migration routes exist; when anti-trafficking policies are delegated to migration control; and when there is limited or no access to borders, the risk of child trafficking and (sexual) exploitation increases. Limited or lack of adequate access to protection and essential services – most common in hostile environments - leave child migrants at the mercy of smugglers and traffickers.

Within the latest report, “Tipping Points to Turning Points”, Save the Children urgently calls for governments, donors, humanitarian and development agencies, service providers, and local communities to:

- Strengthen protection and assistance for migrant children by offering coordinated, cross-border, needs-based support at all critical junctures along the route.

- Advocate to establish and expand safe, regular migration pathways.

- Support authorities to shift their focus from criminalisation to victimisation.

- Implement child-sensitive anti-trafficking laws and policies.

- Ensure migrant children are treated as children first and foremost.

- Invest in long-term, sustainable solutions as part of return and reintegration programmes.

*Names have been changed to protect identities