Breaking barriers so that all children with disabilities can learn

First published on Huffington Post.

Fred was born blind. Growing up in rural Malawi, there was no expectation that he would get an education, and the village school was not set up to meet his needs. He isn’t alone. It’s estimated that as many as 120 million children in developing countries have a disability, and that 90% of these children are outside the classroom.

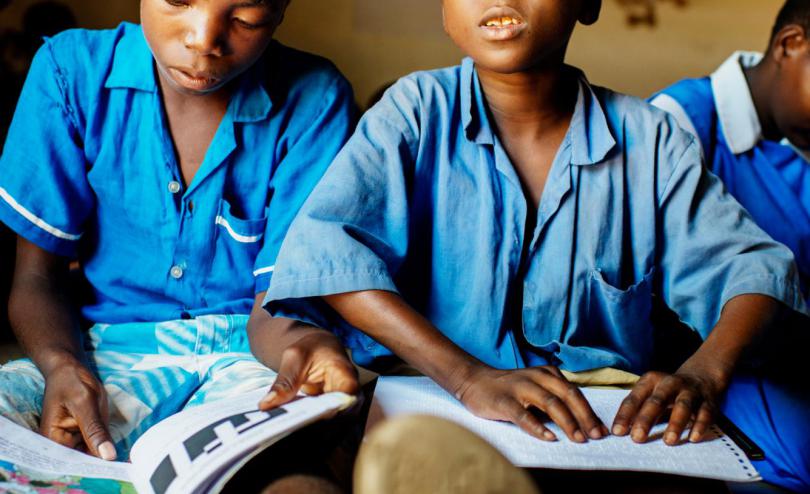

But Fred was lucky. He is now attending a Save the Children-support primary school where he learns using Braille, and is taught by specialist teachers that support his needs. He is positive about his future, and is animated about his friends at school, and what he’s learning.

Today marks a milestone, one decade on from the drafting of the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities. The Convention reflects a fundamental challenge to how societies view and treat people with disabilities, in its bold vision for a shift from protection and charity to rights and dignity.

But for millions of children, the vision laid out in the Convention remains a distant promise. Millions of children with disabilities are invisible within their communities, kept hidden away from public view, and are under-counted or ignored in official data, leaving governments ill-equipped to respond to their needs. Children with disabilities are at three to four times higher a risk of violence than other children. They are the single group of children least likely to learn, and most likely to die early.

Disability is both an effect and cause of poverty and exclusion. The poorer the country, the larger the proportion of children with disabilities – birth complications that are left medically unattended; disease and infection; permanent injuries sustained in conflict; and road accidents all contribute. But disability also reinforces a cycle of disadvantage, through barriers to essential services and the costs of support left to already stretched families.

Childhood is often described as a window of opportunity where, with the right interventions, it’s possible to break that cycle. But too often, the window is firmly shut for children with disabilities. Scarce resources explain some of this challenge. But prejudice and active discrimination, from the community level up to public policy, also have a corrosive effect on the commitment to act. “There are a lot of people that make trouble for me because I’m blind, but I can’t help it. I have not chosen to be blind,” says Fred. “Both adults and many students tease me. Some adults say I am worth nothing.”

The positive news is that these barriers to survival and learning are increasingly recognised. Campaign organisations, many of them led by people with disabilities, played a crucial role in securing specific commitments in the UN Sustainable Development Goals to progress for people with disabilities in education and employment, and to disaggregated data.

Public opinion supports this shift. Earlier this year, a global opinion poll commissioned by Save the Children found that 80 percent of people are concerned that children with disabilities are being excluded from education and healthcare, and believe that governments have the responsibility to act.

The agenda is clear. Governments must invest in education that’s genuinely accessible and appropriate for children with disabilities, and poorer countries need international aid donors to support these efforts. Laws and policies that actively discriminate, or have the same effect by failing to recognise specific needs, must be challenged and changed. Campaign organisations, working in creative partnerships with opinion-shapers, can confront stigma and shift public attitudes.

This is why Save the Children is campaigning to ensure that every last child with disabilities is in school and learning. This is a smart agenda, as well as being the right thing to do. Put simply, international targets to tackle poverty cannot be met unless we tackle the exclusion of millions of children on account of their disability. The time to act is now.